The Silk Road: The World’s First Internet

How trade, ideas, and disease linked continents.

INTRO — A NETWORK LONG BEFORE WI-FI

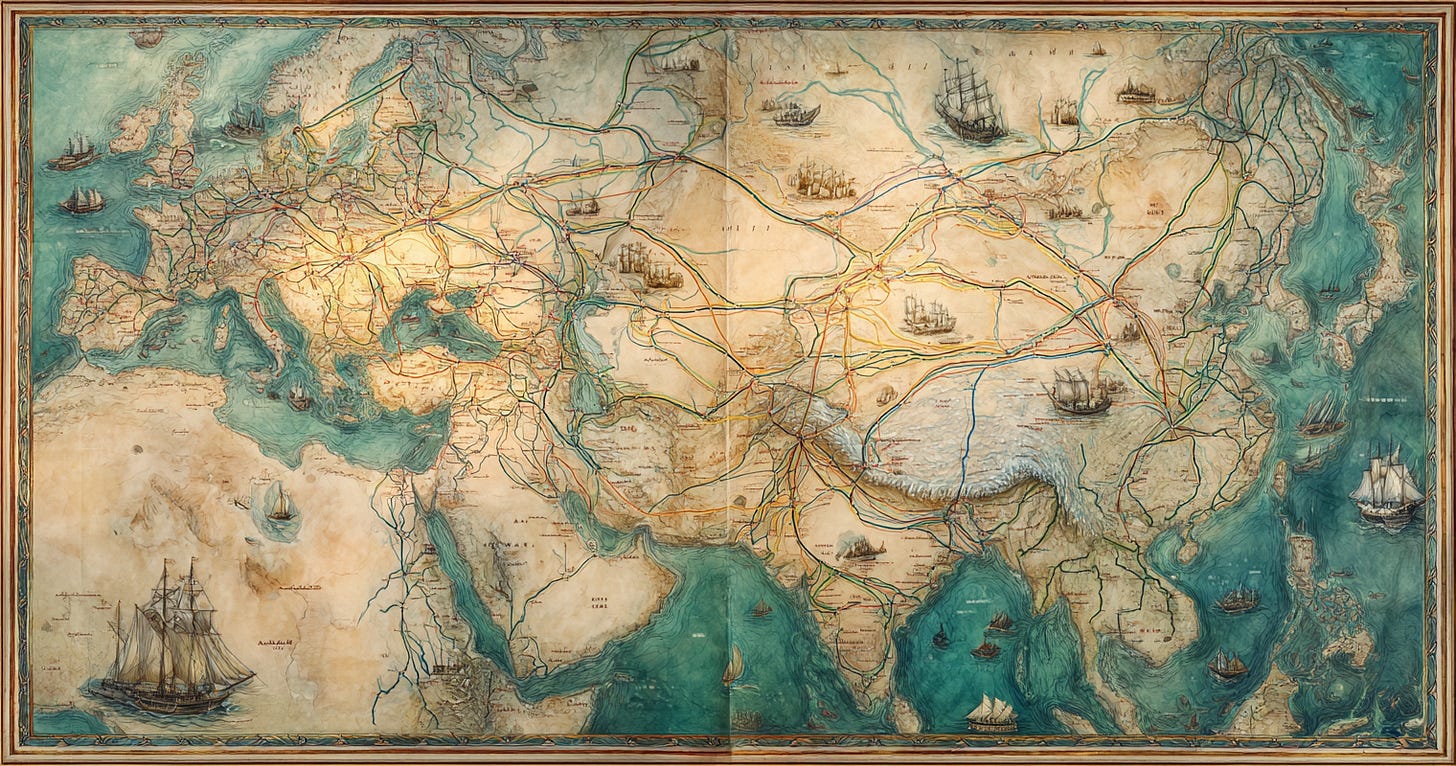

The Silk Road wasn’t a single road cutting across deserts like a dramatic movie scene.

It was a sprawling, shifting, ever-changing network of trade routes connecting China, Central Asia, India, Persia, Arabia, and the Mediterranean.

It moved far more than silk.

It moved religions, technologies, artistic styles, languages, diplomats, soldiers, medicine — and sometimes plague.

The Silk Road wasn’t just a trade route.

It was a communication network — a global internet made of caravans, ships, markets, and merchants who carried ideas as easily as they carried silk.

It didn’t just move goods.

It moved civilizations.

PART I — WHY SILK BECAME THE WORLD’S FIRST LUXURY VIRAL PRODUCT

Silk was ancient China’s superweapon — a soft, shimmering fiber worth more than gold in Rome.

No other product ignited such desire across continents. Chinese sericulturists guarded its secrets so fiercely that smuggling silkworms was punishable by death.

But the appeal of silk didn’t travel alone.

Merchants carried lacquerware, jade, porcelain, and paper.

In exchange, they brought back glass, ivory, silverwork, spices, and horses.

Trade wasn’t one-directional — it was a cultural handshake.

And everyone wanted a piece of it.

PART II — THE PEOPLE WHO MADE THE SILK ROAD RUN

The Silk Road wasn’t dominated by any single empire.

It relied on smaller, specialized cultures who knew how to survive and profit in their specific terrains.

Sogdian merchants carried goods between China and Persia.

Persian traders guarded their networks from Mesopotamia to India.

Central Asian nomads offered protection — or demanded it.

Tibetan caravans navigated high mountain passes.

Indian traders connected overland goods to maritime routes.

Without these multi-ethnic networks — of translators, guides, traders, and negotiators — the Silk Road wouldn’t have existed.

It wasn’t geography that made the Silk Road possible.

It was people.

PART III — CITIES THAT ROSE BECAUSE OF TRADE

Some cities became legendary because of Silk Road wealth:

Samarkand glittered with blue mosaics.

Bukhara thrived as a center of scholarship.

Dunhuang became a fortress of Buddhist art.

Kashgar turned into a crossroads of Persian, Chinese, Turkic, and Arab cultures.

These weren’t cities that passively sat on a map — they were engines of exchange.

Ideas collided as easily as goods.

A traveler could hear Sanskrit prayers in one street, Persian poetry in the next, and Chinese merchants haggling in another.

Civilization didn’t just pass through these cities.

It was remade in them.

PART IV — MORE THAN GOODS: THE MOVEMENT OF IDEAS AND RELIGIONS

The Silk Road was history’s most successful cultural delivery service.

Buddhism traveled from India to China, thanks to monks carrying sutras through mountain passes.

Chinese envoys brought back new styles of painting, music, and astronomy.

Persian merchants introduced new textiles and administrative practices.

Greek medicine spread eastward, influencing Chinese treatments.

Even cuisine traveled.

Noodles crossed borders.

Spices seeped into kitchens.

Tea spread slowly but inevitably.

It was globalization before the word existed.

PART V — EMPIRES THAT SHAPED THE ROUTES

The Silk Road thrived not during peace alone, but under the right empires.

The Han Dynasty secured the eastern routes.

The Kushans stabilized mountain passes.

The Sassanids enriched Persian corridors.

The Tang Dynasty turned Chang’an into the greatest capital on earth.

The Islamic Caliphates connected markets from Spain to India.

And the Mongols, centuries later, united the entire network under one imperial roof.

Every strong empire carved a smoother path.

Every collapse fractured the routes.

The Silk Road was always a mirror of the world’s political landscape — shifting with borders, bandits, alliances, and wars.

PART VI — DISEASE ON THE MOVE: THE DARK SIDE OF CONNECTION

The same routes that welcomed monks and merchants also carried something less pleasant — plague.

One of the earliest major pandemics likely traveled along Silk Road arteries, eventually reaching the Mediterranean. Later, even the Black Death may have followed Steppe trade routes into Europe.

Connectivity wasn’t always a gift.

Civilizations paid a price for their curiosity.

PART VII — THE DECLINE: WHEN OCEANS OUTCOMPETED DESERTS

The Silk Road didn’t end abruptly — it faded.

Maritime trade became faster and cheaper.

Empires that once stabilized the routes fragmented.

New powers prioritized coastlines over caravans.

Banditry surged.

Cities declined.

Deserts reclaimed pathways.

By the 16th century, the Silk Road had become a shadow of its former self.

But its legacy didn’t disappear.

It simply transformed.

CONCLUSION — THE FIRST GLOBAL NETWORK

The Silk Road’s true significance isn’t in the caravans or the silk.

It is in the connections it created:

between empires

between religions

between ideas

between people

It demonstrated that no civilization stands alone — and that the world becomes richer (and occasionally more dangerous) when paths cross.

Long before fiber-optic cables and shipping lanes, the Silk Road tied continents together.

It was, in every meaningful sense, the world’s first internet.